Silver-Colored

The word Argentina is derived from the Latin word for silver, argentum, making the country of Argentina “silver-colored”. The name of the country itself traces its roots back to a poem, written in 1602, entitled La Argentina and attributed to Spanish explorer Martin del Barco Centenera. Its ten-thousand verse length outlines the conquest of the territories, as well as the country’s breathtaking landscape. La Argentina is also the first installment in the long, storied, and beautiful tradition of Argentine literature.

José Hernandez, Argentine federalist writer.

Since becoming a fully unified entity in the 1850s, Argentina has developed one of the South American region’s most active publishing industries, as well as developing a roster of Latin America’s most prominent writers. At that time, the primary literary discourse was between two major ideologies – the Federalists, like José Hernandez, emphasized rural conservatism and demonized “Europeanization”, while the Unitarians, like Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, advocated for strong centralized government and open immigration. As with many emerging countries, the literature at the dawn of Argentina’s organization was fiercely nationalist. Even with the drafting of a constit]ution and a nation-building plan, there was no shortage of ideas on how to run the country – a streak that continued well into the modern age.

Publicity still for Almafuerte (1949), a biopic of the poet of the same name.

The 1880s saw a rising movement emphasizing the cultural excellence of Buenos Aires. Poets such as Almafuerte (pen name of Pedro Bonifacio Palacios, meaning strong soul) criticized the societal change of focus from village to metropolis, and celebrated the everyday struggles of the working class. Elsewhere, essays and realism dominated the scene, alternating between the social issues of the day and popular folk literature.

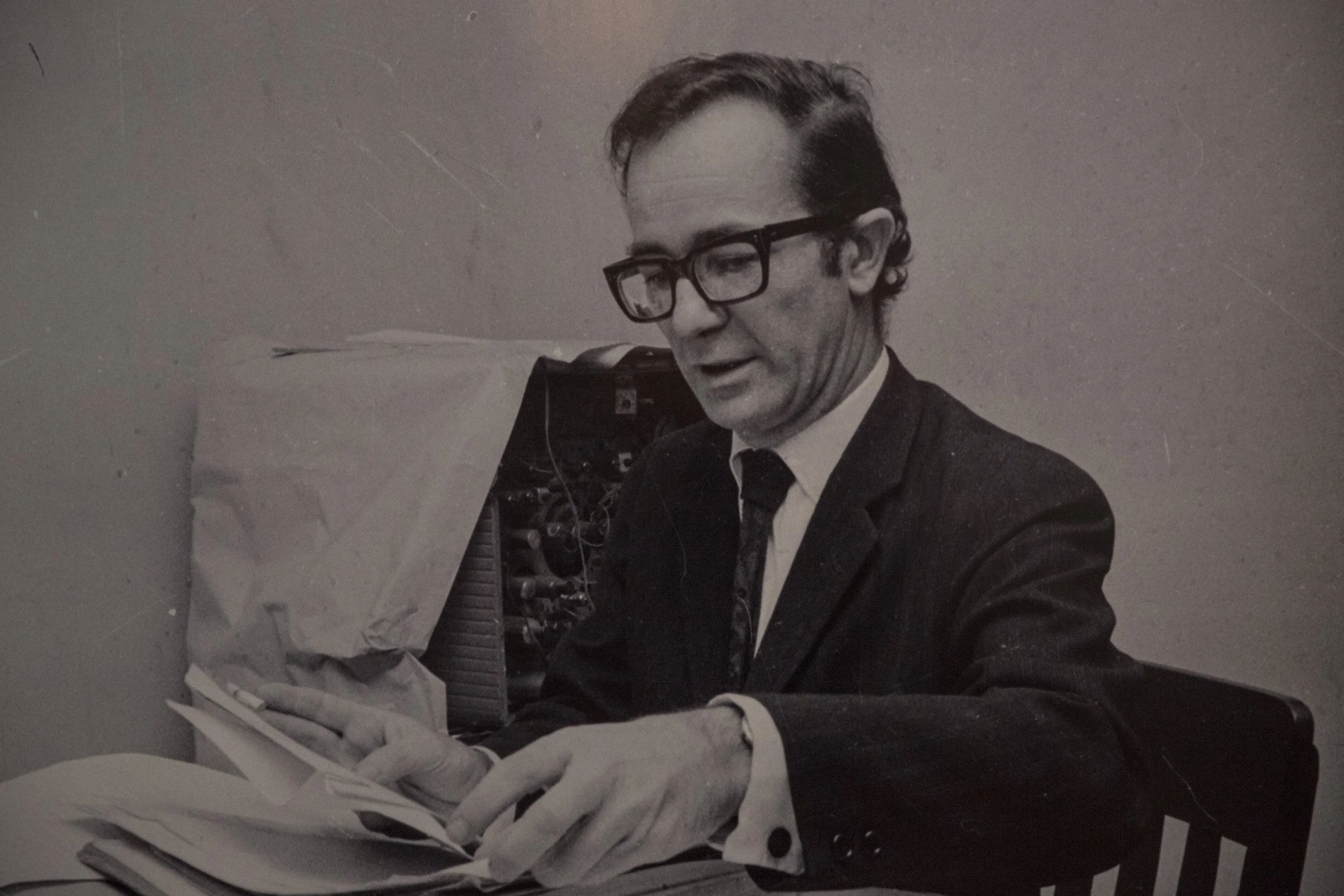

Julio Cortazar.

With the dawn of the twentieth century, many literary movements began to coalesce and form new offshoots. This era gave rise to the first works of legendary authors Jorge Luis Borges and Benito Lynch, both future pioneers of magical realism in literature, yet distinct from one another in voice, style, and subject. They, along with countless others, laid the groundwork for similarly idealistic poets of the early 20th century like Julio Cortazar, Silvina & Victoria Ocampo, and Vicente Barbieri. The aftermath of World War II gave rise to even more intellectual reactions, particularly existentialism (influenced in turn by European philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus) and avant-garde prose. Prominent essayists did not particularly abound in the early 20th century, though they would see a resurgence in the 1970s, during the Dirty War – perhaps most famous of all, martyred journalist Rodolfo Walsh, considered the father of Argentine investigative journalism.

Rodolfo Walsh, journalist and publisher of Open Letter from a Writer to the Military Junta.

He was murdered by state terrorists during the Dirty War.

Today, as with other universal aspects of national identity, the bodies of work that comprise Argentine literature undergo continuous reevaluation – for as Argentines know better than most, democracy cannot flourish and adapt to the future without the continuous introduction and testing of new ideas.